Movie-Hype00683 - BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID

As I mentioned a few days ago, I have a Great Movie Shame List, films I should have seen (as an SMF, a serious Movie Fan), but for some reason haven’t. I’ve been working my way steadily through the List, lately spending a lot of time in the late ‘60s/early ‘70s.

There are some fantastic films of the era, as I’ve re-discovered with MEAN STREETS,

As a student of history I know a bit about Butch Cassidy and his Wild Bunch, both the history and the legend. I was suspicious the movie would bear little semblance to reality, but pledged to treat the film like any Western and not judge it by history.

To show you how much I didn’t know about the film, a few minutes in you find out that Robert Redford is “Sundance,” and instantly a light went off in my head. “Oh. That’s where his film festival gets its name!” I know, I know: I’m an idiot. But I knew so little about this movie, I didn’t even know who played what. I suppose if I’d ever thought about it I might have connected this movie to

While I’m on the subject of

Second was the Macho factor. When a John Wayne or Clint Eastwood walked on screen, you never had a doubt in your mind they’d kill everyone without thinking twice about it. But

For that matter, was

Why is this important? Well, the movie rises of falls on the chemistry between Cassidy (Paul Newman) and

(If nothing else, it makes the acting more impressive if

My next problem was how unserious it all seemed. Only a few minutes in and Paul Newman has Katherine Harris on the handlebars of his bicycle while he clowns around doing tricks, all while B.J. Thomas’s “Raindrops Keep Falling on My Head” plays in full. You can almost imagine John Ford and John Wayne simultaneously throwing up in their own mouths.

(The 1899 version of a souped up Chevy Ragtop)

Not only is the scene beyond silly, but Harris’s Etta just had been in bed with Sundance, her boyfriend. Did this mean there was a Love Triangle thing going on? It’s hard to say. Etta was clearly Sundance’s girl to the bitter end, but seemed to get along much better with the more affable Butch Cassidy. I would have been interested in what a movie might look like with that angle played out. Sadly, it never went anywhere, if it was there in the first place.

The Raindrops song is one of three extended musical sequences, and virtually the only music in the film. The other two are also modern (1969 as opposed to 1900), and composed by Burt Bacharach. I can’t pretend I would have chosen that way to go, but it got more effective the more I got into it (and I’m willing to bet that in future viewings I’ll come to love it.) One sequence is a series of sepia-toned pictures with Butch Cassidy, Sundance and Etta going from the West to

The third musical sequence takes place in

Let’s get back to our two leads. This movie is famous—won 4 Oscars, made the AFI’s top 100 movies of all time, and makes every list of Great Westerns ever—not for the impressive locations or tricky camera work, or for the innovative musical numbers, but for one simple reason: the outstanding, fantastic—arguably top five of all time—chemistry between Newman and Redford.

Without lengthy exposition or back-story or anything these two slip into a rhythm is totally believable. They come across like BFF (Best Friends Forever), but more than that. Think of Bones and Spock, Frodo and Sam, Han and Chewie, Vincent and Jules, Trapper and Hawkeye, Merton and Riggs, Reggie and Jack, Cheech and Chong, Statler and Waldorf, Jay and Silent Bob, Chuck Nolan and Wilson and the entire A-Team all rolled into one.

These two could argue for an hour and then roll into a gun fight without blinking. They—and this is a stretch, but perhaps this is the point—could coexist with a beautiful woman without tearing themselves apart. I have a friend whom I might—might—someday get to this level with, and there’s nothing greater.

[I know this is going to get me into all sorts of trouble, but I feel compelled to admit that the reason female duos are conspicuously left off my pairings isn’t just because Hollywood generally doesn’t write one good female part per movie, let alone two. (And who would it be? Maybe Thelma & Louise? Cagney & Lacey? The Ya-Ya sisterhood?) It has been my experience that women—while definitely capable of same-sex friendships that can be closer than anything men can achieve—don’t have that camaraderie of men. Or chemistry. At least on screen. All the best chemistry involving women is usually a woman and a man. Is this just because of the writing? Maybe. But I doubt it.]

Anyway, to recap the last few paragraphs: movie worth seeing for the two leads.

But there’s another reason to see BUTCH CASSIDY, and here my Film School Psychobabble rears its ugly head. (Actually, I didn’t go to film school, but if I had, I might have learned this.)

BUTCH CASSIDY is a Western, but a very different type. Set at the end of the West, this isn’t Wyatt Earp or Rooster Cogburn in all his glory. While we love and believe these two characters, the film isn’t filled with their incredible exploits. Initially they pull off a smooth robbery, but robbing that same train on the way back the trouble starts. A “Super Posse” made up of legendary Law-man Joe le Fors and a famous Indian tracker (improbably named Lord Baltimore) have been brought together with the sole purpose of catching the Wild Bunch.

The initial encounter eviscerates the gang, leaving only Cassidy and Sundance. From then on the two are on the run. Never is the idea of standing and fighting voiced. These two may be legends, but they aren’t endowed with super powers. They know their only chance is to run, run, and run some more.

We never actually see the Super Posse except at a distance. They are relentless, always coming, always right behind, but are never given personality or form other than a menacing presence. I like this choice by the screenwriter and filmmaker. I also like the courage to portray Butch and Sundance realistically. (This continues to the point where we actually see them reload their weapons time and time again in the big shoot out at the end rather than the normal cinematic experience of FPS-like never-ending bullets.)

I’m not sure if the people involved meant to make this statement, but to me the deeper meaning is that Butch and Sundance represent the dying West.

That whole era was dying by 1900. The West was getting civilized. Train tracks, settlers, towns cropping up everywhere. There was no more room for crazy gunslingers and wild men. Folks might admire the daring of the brave outlaw, but that wasn’t going to stand in the New West.

Watching the Super Posse track Butch Cassidy and Sundance down, watch them slowly implode as the stress gets to them, I saw the metaphor for the entire way of life. It was sad in a way. Inevitable, perhaps, but sad.

One other moment I simply have to mention: In Bolivia Butch and Sundance find themselves obliged to go straight. It is only then that Butch—for the very first time in his life—is forced to kill a man. The impact of this moment—somehow he can’t win for losing, and might as well not even try—is poignant and incredibly sad.

All that’s left is the big ending, and thought it may seem overdrawn, from my own knowledge of history I can tell you they really did bring in that many hundreds of soldiers to hunt these two down. We’re left with our two ant-heroes, surrounded, without a chance, but still wise-cracking and flippant to the bitter end.

Both wounded badly—perhaps mortally—and preparing to go out in a hail of bullets—Butch suddenly asks Sundance in alarm, “Did you see Le Fors (of the Super Posse) out there?”

“No.” replies Sundance. “I didn’t see him.”

“Good.” Butch smiles, relieved. “For a moment, I thought we were in real trouble.”

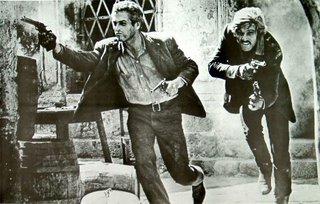

And with that, they two rush out of the building, guns blazing. That’s all we see, as the picture freezes and morphs into one of those pictures from the Old West.

(It doesn't look good, but I'm still holding out hope for a sequel)

It’s fitting, in a way. Every time I see these pictures I’m enraptured by their charm, their simplicity, their evocation of a simpler time and place. In a way the pictures are a simulacrum: the world was never sepia-colored, and the West was never quite like the stories.

But I still am fascinated by those old pictures. They tell such a great story. They seem to bleed with life. And yet, we don’t take pictures like that anymore. We’ve moved on. And we don’t make movies like BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID anymore too.

Maybe it’s inevitable, but it’s still sad.

Note #1: There’s a documentary on the DVD where director George Roy Hill goes through the film in about twenty minutes, explaining his motivations and how/why they shot it that way. He’s extraordinarily candid, and at the end mentions how he’s unsure how the film will be received. That’s right: the documentary was made before the film was released, before it became legend. A definite must-see after watching the movie.

Note #2: 1969 brought us not only BUTCH CASSIDY AND THE SUNDANCE KID, but TRUE GRIT and THE WILD BUNCH, all inarguably on any sane person’s list of Top 15 Westerns ever, making 1969 one hellava year for Westerns.

No comments:

Post a Comment